How do you shrink a government? That is a thorny political question anywhere in the world but especially in Brazil, which has traditionally favoured a bloated state.

Now, however, the new government of interim president Michel Temer is trying to tackle this issue as it grapples with a fiscal crisis that is threatening to unwind the country’s economic achievements of recent decades. Sign up now

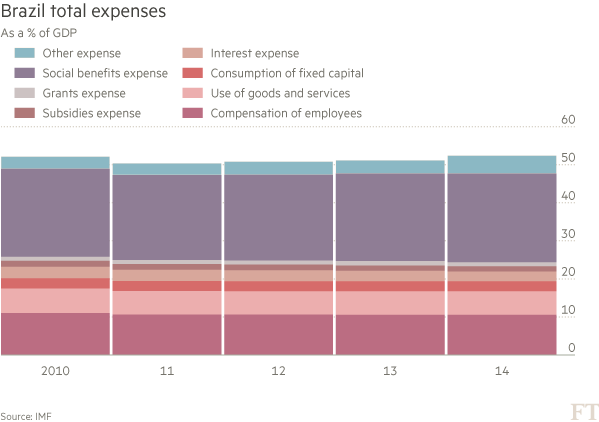

Mr Temer’s answer is as bold as it is unorthodox — a constitutional amendment to freeze for the foreseeable future public expenses in real terms at 2016 levels. If implemented, the move could help cure one of Brazil’s biggest ills — a spendthrift budget with constitutionally mandated expenditures that have led to constant increases in government spending. This has been exacerbated by a blowout in spending by the previous governments of the leftist Workers’ Party, or PT.

“I’m very encouraged by this,” said Raul Velloso, an economist and specialist on Brazil’s budget. “If we manage to do this, we will free ourselves of the possibility of future populist experiments.”

Brought to power after congress voted in May to begin impeachment proceedings against President Dilma Rousseff, Mr Temer and his supporters in congress have staked their rule on solving a deep economic crisis afflicting Brazil.

The economic dip was fanned by a fall in commodities prices but its ferocity is due to a crisis of confidence among investors in the ability of Ms Rousseff to restore Brazil’s sinking public finances after more than five years in power.

If gross domestic product in the first three months of this year declined again as expected when the figures were announced on Wednesday, in just two years, Brazil’s per capita real GDP would have declined by nearly 10 per cent, Goldman Sachs economist Alberto Ramos said in a report.

This would exceed the 7.6 per cent contraction in the economy during the country’s so-called “lost decade” of the 1980s, a period of runaway inflation. He said he expected the economy would start to bottom out during the second half on stabilising sentiment amid hopes “the new administration will be able to boost domestic confidence by showing tangible progress on the fiscal consolidation agenda”.

Mindful of the need to satisfy investors’ hopes, Mr Temer’s first success as interim leader was to pass a new bill this month setting a more “realistic” target for the budget.

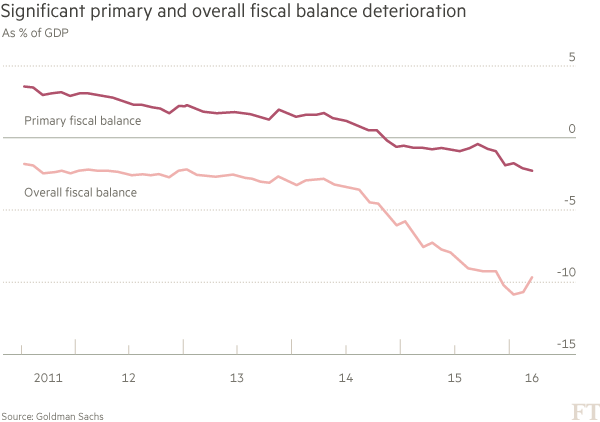

The bill envisaged a primary fiscal deficit — the balance before interest payments, considered a key gauge of fiscal health in Brazil — at a record of nearly R$171bn for the central government, or 2.75 per cent of GDP. This was up from R$97bn set by Ms Rousseff.

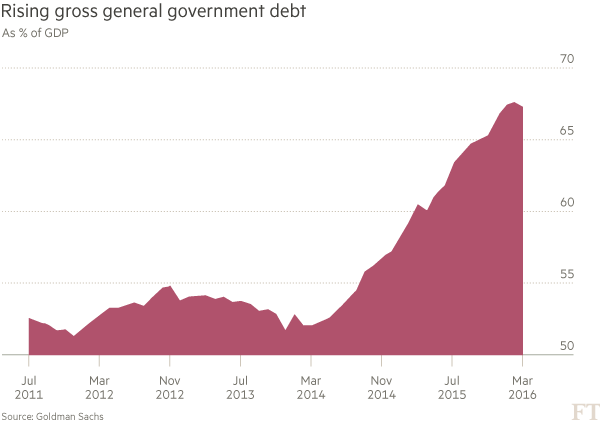

Once interest rate payments are added, the total deficit for the central government is running at around 10 per cent. This is driving government debt up, placing an enormous strain on the budget with the benchmark Selic rate at 14.25 per cent

To help solve this, the government is proposing a law restricting any future increases in budgetary spending to the past year’s inflation.

To implement the law, the government will need to propose a constitutional amendment delinking certain dedicated revenue streams from health and education. It will also in the longer term have to change linkages between the minimum wage and public sector salaries and pensions, a tough issue with the unions.

The law would help freeze a constant increase in the size of the Brazilian state. Central government spending alone has risen from 14 per cent of GDP in 1997 to 18.6 per cent in 2015. The overall government including states and municipalities spends about 40 per cent of GDP — the equivalent of an advanced economy without the services.

In a report, Moody’s Investors Service described the proposals as short on detail and “arduous” to implement and said it did not see a clear path to implementing structural reforms.

“It’s very across-the-board, you could call it a blunt instrument,” Samar Maziad, a senior analyst at Moody’s said of the budget expenses limit. “The important point is to know what exactly is going to be cut and this is why we don’t have enough information.”

David Beker, an economist with Bank of America Merrill Lynch, said the measure looked “aggressive”. One problem was that it did not allow for countercyclical policy for future economic crises.

“Normally, you discuss every single year depending on the situation, what you expect for the following year in terms of expenditures,” Mr Beker said.

However, Mr Velloso said once the economy started growing again, tax revenues would rise at a faster rate than inflation, allowing the government to accumulate ever greater primary fiscal surpluses and pay down debt.

He said the crisis had created an ideal opportunity to pass such difficult measures. Since most of congress had supported the impeachment, members needed to support Mr Temer’s measures to resurrect the economy or risk being collectively blamed for Brazil’s situation.

“Temer can go to congress and say: ‘Listen, if we commit an error here, we’ll all be held responsible for the disaster’. We can’t let that happen,” Mr Velloso said.

No comments:

Post a Comment