- Many who had pulled out of poverty are now falling back in

- ‘It doesn’t feel like Christmas at all,’ one shop owner says

Few Brazilians will mourn the passing of 2016. The president was impeached, a vast corruption scandal dominated the headlines day after day and a devastating recession - the worst on record - crushed the hopes of millions.

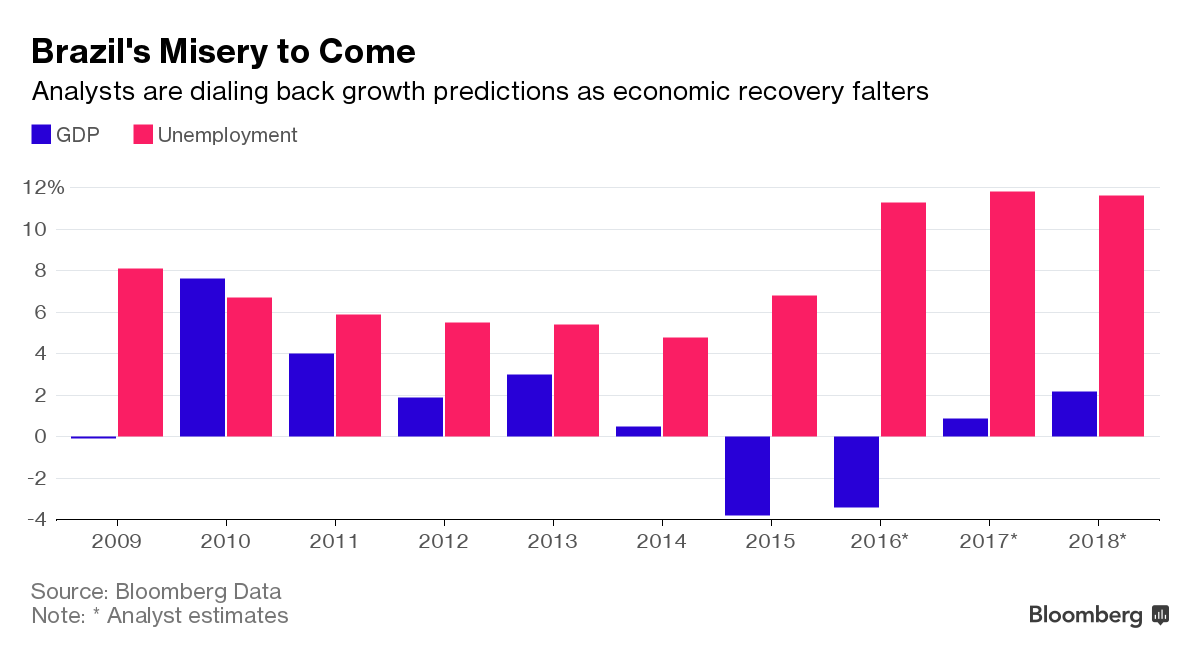

It is that last element that remains the most painful today. For while financial markets have rebounded as the new administration sought to calm jittery investors, the economy is showing precious few signs of improving. And most analysts are now dialing back 2017 growth predictions to almost zero.

In Brasilia, the capital city and home to the highest income per capita in this nation of 206 million, shop owners complain about one of the worst Christmas seasons ever. Asked how business was going at his electronics store, Antonio Renato Pires returned a blank stare and, after a long period of silence, said: "Terrible."

"It doesn’t feel like Christmas at all."

Signs of economic malaise abound throughout the country and across social classes as Brazil’s recession proves to be deeper and more persistent than most had expected. Gross domestic product is estimated to have fallen more than 7 percent in two years, causing unemployment to nearly triple. At least 10 percent of the 35 million people that emerged from poverty in the decade through 2014 have fallen back down the social ladder again.

Losing out

Mariana Nunes, who holds a Master’s Degree in marketing and worked at a major telecommunications company in Brasilia, until 2014 had a maid, private health insurance , and went out to a bar or a show once a week. She even traveled to the U.S. twice. Today, she lost all those perks, defaulted on 5,000 reais ($1,501) in credit card debt and sells home-made cakes to get by.

It has been particularly painful for those Brazilians who had just begun to taste the comforts of middle class-life before having to give them up again. "It’s harder to lose something you acquired than remaining where you are," said Marcelo Neri, director of the social policy center at the Getulio Vargas Institute, a business school and think tank.

The institute’s social policy center estimates that the country’s poverty rate jumped from 8.3 percent to 10 percent between 2014 and 2015, an increase that Neri says accelerated further this year.

Pedestrians pass in front of a newsstand in Sao Paulo.

The social security network that had provided some relief to the nation’s poorest is showing signs of crumbling as well, as the recession eroded tax revenue and forced several states to declare a state of financial emergency.

Battered by a debt crisis, Rio de Janeiro state recently shut down most of the so-called citizen restaurants that served a basic meal for 2 reais ($0.60). That puts an extra burden on Jordelio Ferreira, a 42-year-old street vendor, to feed himself and his family.

"I used to eat lunch there sometimes,” he said sitting on the street curb under a makeshift umbrella with his wife and toddler by his side. “Now we have to make do somehow." The standard box lunch with rice, beans and a small piece of meat costs upward of 15 reais ($4.5).

Brazil’s upper middle class is also feeling the recession, albeit on a different scale. At a private school in Brasilia’s upscale Lago Sul neighborhood parents recently organized a used-book sale for the first time ever to help meet the $750-per-child cost of new books.

Public services such as education and health, which had already been overburdened before the recession and became the focus of mass street protests in 2013, are struggling to cope with the influx of students and patients who could no longer afford private schools or health insurance.

For Sale Signs are displayed in front of a vacant property in Sao Paulo

Taina Caldas, a 20 year-old psychology student from Rio de Janeiro, tried to keep her sore throat at bay for four days until a sleepless night drove her to a state-run first-aid unit, or UPA by its Portuguese acronym, for the first time in her life. Her mom had canceled the family’s private health insurance a few months after she lost her job managing a store.

“We couldn’t keep paying,” Caldas said during her two-and-a-half-hour wait. “I confess I didn’t want to come to an UPA. I always went to private hospitals. I asked my mom to come along to show me how to do everything.”

According to the clinic’s medical coordinator, Maria Christina Tavares, former private patients now account for roughly 25 percent of those attended to, adding an hour to the typical wait for low-risk patients. As part of further cost-cutting measures the unit is unable to provide drugs for patients who don’t stay overnight.

After the party, the hangover

One of the reasons Brazil’s crisis is deeper and longer than many had forecast is that much of the growth that preceded it, had been artificially sustained by subsidized loans, tax breaks, and price caps that fueled consumption but also staggering levels of debt that now prevent investment and consumption.

"Companies are in debt, families are in debt, and banks have cash but are unwilling to lend," said Carlos Thadeu de Freitas, chief economist at the National Commerce Confederation in Rio de Janeiro.

Economists surveyed by the central bank have slashed their 2017 growth estimates to 0.6 percent from 1.4 percent only three months ago. Credit Suisse and Bradesco forecast no growth and a 0.3 percent expansion next year, respectively.

Indeed for many people, Christmas may be grim next year too, according to Carlos Henrique Corseuil, an economist at the government-run economic think tank Ipea. He sees unemployment rising further in coming months before leveling off in the second half of next year. To experience a true economic rebound, he said, Brazilians will have to wait at least until 2018.

No comments:

Post a Comment