Venezuela’s Trade Scheme With Turkey Is Enriching a Mysterious Maduro Crony

Investigators say retrofitted criminal networks are being used to trade gold for the food that’s propping up the regime.

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, right, presents the Order of the Liberator to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan at Miraflores Palace in Caracas in December 2018.

PHOTOGRAPHER: CEM OKSUZ/ANADOLU AGENCY/GETTY IMAGES

In the late afternoon of July 15, 2016, a cluster of staffers inside the Turkish Embassy in Caracas struggled to make sense of the images from home flashing across their televisions and computer screens. Military trucks were blocking a bridge over the Bosporus, tanks were rolling into the Istanbul airport, and smoke was rising from the streets of Ankara. As best they could tell, a group within the Turkish military was trying to overthrow the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Imdat Oner, the chargé d’affaires of Turkey’s diplomatic mission in Venezuela, was straining to hear a live news report when a telephone rang, pulling him away from his colleagues. On the line was Samuel Moncada, Venezuela’s deputy foreign minister. Oner knew him, but not well. He didn’t feel he knew any of the Venezuelans well, because the relationship between Turkey and Nicolás Maduro’s government seemed to him superficial, at best.

For a decade, Turkey had been trying to jump-start trade with Latin America, but Venezuela remained a dead zone. Hugo Chávez, Maduro’s predecessor, had regularly slammed Turkey for its opposition to Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, a Venezuelan ally. Shortly after Chávez’s death in March 2013, Turkey, as a way to kindle economic ties, tried to sell Maduro on a Turkish Airlines route connecting Istanbul and Caracas. He ignored the approach, says Oner. Even after Venezuela’s economy fell headlong into an extended and ongoing economic collapse, Turkey’s offers to trade food and pharmaceutical products for Venezuelan oil derivatives went nowhere.

Given the history, Oner was caught off guard by the message now being delivered on behalf of Maduro—a promise of unflinching solidarity with Erdogan in the face of “external meddling.” Maduro seemed convinced that the U.S. had orchestrated the Turkish uprising, just as he accused the Americans of being behind an unsuccessful 2002 coup attempt against Chávez.

Erdogan came to agree with him. In the months after the uprising, Turkey stripped hundreds of diplomats of their titles, labeling them supporters of a U.S.-backed overthrow attempt. Oner left the government as this was happening, and now is pursuing a doctorate degree in Florida. And Erdogan hasn’t forgotten Maduro’s pledge of support. He’s since complained that almost every leader in Europe remained silent for days after the failed plot. But not Maduro. “With the coup attempt,” Erdogan said at a news conference earlier this year, “we met Maduro. It has been a good beginning.”

Maduro and Erdogan in Istanbul in October 2016.

PHOTOGRAPHER: KAYHAN OZER/ANADOLU AGENCY/GETTY IMAGES

Within weeks of the July call, Maduro announced his first trip to Turkey. Before the end of 2016, that Turkish Airlines route between Istanbul and Caracas was inaugurated, and delegations from the two countries started crisscrossing the Atlantic to forge deals. They began to construct a secretive business network, one that could operate out of reach of financial sanctions imposed by the U.S. It would be a network that trades in two powerful currencies for Venezuela: gold and food.

Maduro was saddled with a near-worthless currency, the bolívar, that had been bludgeoned by years of hyperinflation. Profits from his country’s massive oil reserves, which had funded the Venezuelan government for decades, were evaporating because of falling prices, a neglected and crumbling infrastructure, rampant corruption, and international isolation. Venezuelans were starving, and Maduro’s approval rating had plummeted. So he grasped a financial lifeline in gold, one of the only resources of value he had left.

In August 2016, Maduro announced that a state mining company called Minerven would be the sole official gold buyer in the vast tracts of jungle, savanna, and rolling hills where mining had long been clandestine and unregulated—essentially legalizing a business lorded over by murderous gangs. He sent in troops to force miners to comply and began hoovering up ore from open-pit mines. (Through a spokesman, Victor Cano, the mining minister, declined to comment for this story.) Maduro also started cashing in on the billions of dollars’ worth of gold bars that Chávez, who was loath to invest in U.S. dollars, had stockpiled. The sell-off carried hints of desperation. According to sources in Venezuela’s central bank, the government secretly sold the bank’s massive collection of rare gold coins, dating to the 18th century. The coins, box upon box of them, were thrown together in a single 30-ton sale in late 2017, and Venezuela accepted a price based on their weight alone, not their collectible value.

By then, Maduro was weathering extensive U.S. sanctions—mostly targeting individuals in his government accused of corruption, human-rights violations, and other crimes—and he seemed to anticipate that the U.S. Treasury might next sanction his dealings in gold to further choke the economy. Venezuela had been shipping freshly mined gold abroad, primarily to Switzerland, for processing. Last July, Maduro began sending it to Turkey. He’d already shipped at least $900 million in gold there by the time the U.S. last fall banned American individuals, banks, and corporations from doing business with anyone connected to Venezuelan gold sales. Tons more have gone since. The Turkish government declined to comment on allegations of wrongdoing related to the gold trade.

A gold-processing facility owned by Minerven in El Callao, which Bloomberg has called Venezuela’s most dangerous town.

PHOTOGRAPHER: MANAURE QUINTERO/BLOOMBERG

Venezuela now finds its business partnership with Turkey in the crosshairs of several law enforcement organizations around the world. Investigators from at least three countries, including the U.S., believe Venezuela’s gold and food trade with Turkey has evolved into a multilayered scheme built on a foundation of criminality. The pursuit of the gold trade has become a key part of a larger U.S.-led effort to further isolate Venezuela’s economy and force Maduro to release his hold on power.

“In many ways, gold is the key to the survival of Maduro’s government,” says Americo De Grazia, an opposition lawmaker who represents Venezuela’s main gold-producing region in the southern state of Bolívar, the Arco Minero del Orinoco, or Mining Arc. “But I’m not talking so much about the programs and functioning of the state. I am talking more about maintaining the perverse fortunes of key figures inside the government.”

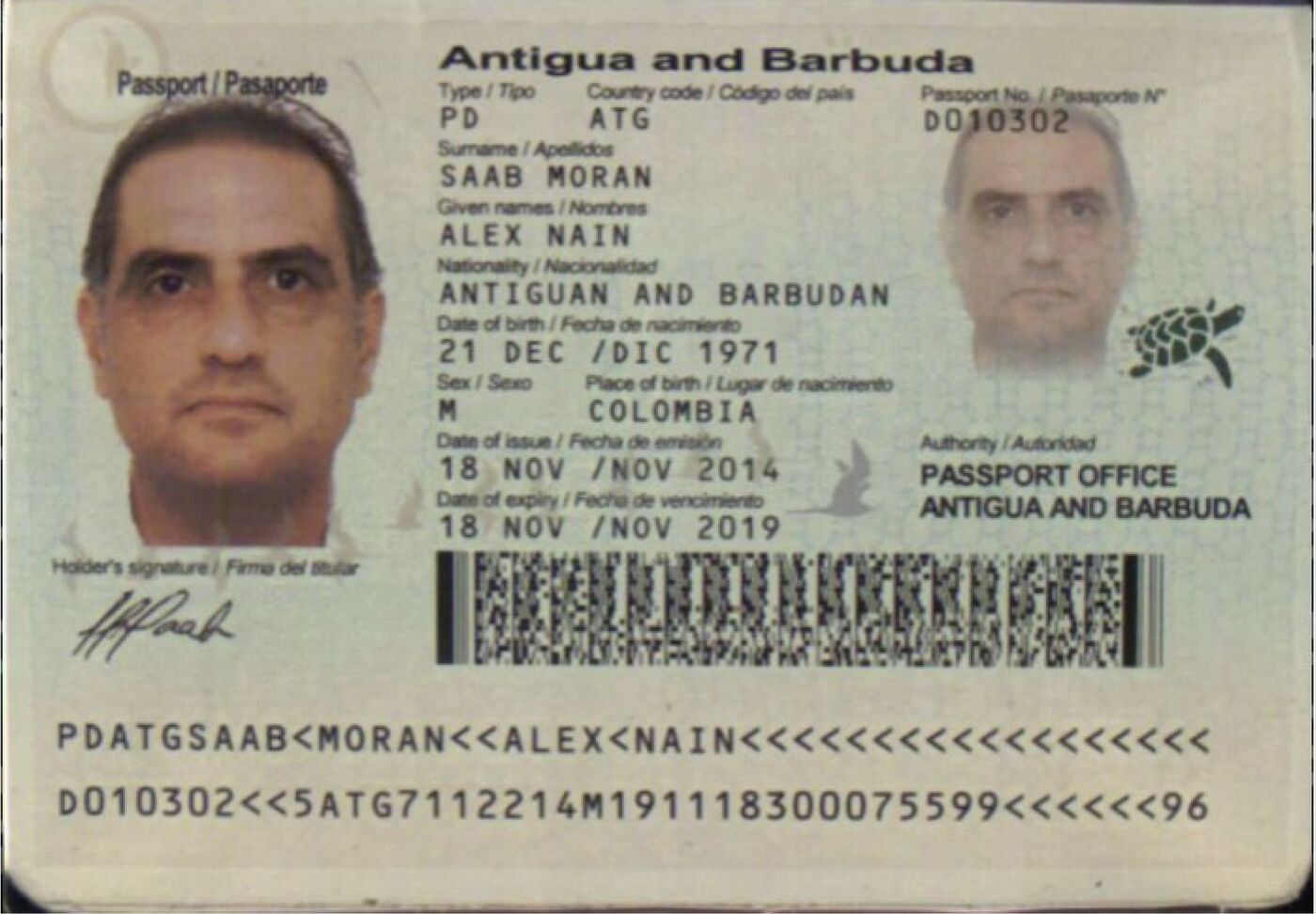

At the center of it all is a Colombian named Alex Nain Saab Moran, whom U.S. investigators believe to be one of the most powerful financial enablers of Maduro’s regime. An examination of Saab’s international business empire and the allegations against it provides a lens into the uncharted territory that Venezuela has now entered: a place of strangled isolation, where millions suffer while the regime is encircled by opponents, all of them trying to break its last remaining links to economic survival.

This is the passport Antigua and Barbuda gave him and now says it will revoke.

SOURCE: INTERPOL

For more than a decade, law enforcement agencies in the U.S. and Latin America have been compiling evidence that South American drug traffickers were working with Venezuela’s government to move cocaine and launder money. They tapped phones, tracked international shipments, and built suspect profiles. Several years ago, Saab’s name began popping up with notable frequency, according to people involved in those investigations. In recent months, thanks to the gold and food trade between Venezuela and Turkey, Saab has reemerged as a target of major criminal investigations in the U.S. and Colombia. Opposition lawmakers and former prosecutors from Venezuela are also looking into Saab. The working premise is that he and others have retrofitted their criminal enterprises to adapt to challenges and opportunities. Saab is at the center of sweeping criminal investigations by the U.S. Justice Department and agents from Homeland Security Investigations, four people familiar with the probes say. One focus is whether the food and gold trade with Turkey is being used to launder the proceeds of corruption and to evade U.S. sanctions, these people say.

Saab, 47, is a Colombian of Lebanese descent whose immigrant father, Luis, started Textiles Saab, a successful maker of towels and sheets in the port city of Barranquilla. As a child, Saab attended the German School, a private academy for the city’s elite. After graduation, he dabbled in a variety of small-scale commercial enterprises—“I started working when I was 18,” he said in a rare interview in 2017 with the Bogotá newspaper El Tiempo. Saab started selling pens imprinted with corporate logos and by the time he was 19 had opened a T-shirt factory that ended up exporting to Mexico, the U.S., and Venezuela.

Those who’ve known Saab for decades say he never hid his ambition to be wealthy. When he cruised the streets of the gritty port town in those days, he did so from behind the wheel of his Hummer, according to news reports. His father still leads a sort of booster organization for law enforcement in Barranquilla, called Policía Cívica, or Civic Police. In a brief telephone exchange with Bloomberg Businessweek, he shakes off any suggestion that his son lords over an international criminal network on behalf of Venezuela’s top leaders. “No, I don’t have any knowledge about that case,” he says. The countries investigating his son, he suggests, are doing so to apply more pressure on Venezuela, a sovereign country still struggling to free itself from foreign meddling. “The problem in Venezuela,” he adds, “is for the Venezuelans.”

Barranquilla had long been a conduit for drug smuggling and illicit money flows, and for years investigators in Colombia and at the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration have kept a wary eye on Saab. In the early 2000s he created a network of export companies and listed his family members as representatives or officers, Colombian court documents and business records show. The DEA, in a confidential memo cited by Colombian National Police in a report for prosecutors in Bogotá, described Saab as running a vast money laundering network and identified at least six companies in and around Barranquilla that allegedly move illicit funds abroad. Saab didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment for this story, or to written questions submitted to two of his lawyers. In the El Tiempo interview, he denied being involved in corrupt contracts with Venezuela: “I am an open book, and my accounts are clear and my conscience is clean,” he said. Spokespeople for Colombia’s Attorney General’s Office, the U.S. Department of Justice, Homeland Security Investigations, and the DEA all declined to comment.

Saab’s developing relationship with the Venezuelan government turned him into one of the region’s most powerful men. In November 2011, a company of Saab’s, Fondo Global de Construccion, landed a lucrative contract to supply prefabricated housing units for one of Chávez’s signature projects: expansive public housing developments. In a signing ceremony in the Miraflores presidential palace in Caracas, Saab sat at a table with Chávez, his then-vice president, Maduro, and then-Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos. As part of the deal, some prefab housing panels would be built in Ecuador, then shipped to Colombia via the Panama Canal, and finally trucked overland on a long trip to Caracas.

The route raised suspicions among Ecuadorian customs inspectors, who couldn’t figure out why it was necessary to move the panels through Colombia at all. The Ecuadorians reached out to Juan Ricardo Ortega, then the director general of Colombia’s customs agency. He started to dig and began to suspect that Fondo Global was moving something illicit with the housing panels. By the time Ortega’s agents were ready to move in to inspect the shipments, he says, they mysteriously stopped being routed through Colombia. In late 2013, an Ecuadorian court opened a criminal case after prosecutors said the contract was part of a scheme that allowed Saab’s business partners to launder more than $130 million in illicit funds via fake exports to Venezuela, court transcripts show. Saab himself wasn’t accused of wrongdoing.

Ecuadorian courts eventually dropped the case against Saab’s partners after several years of investigation. By the end of 2014, Ortega resigned, ending any probe in Colombia. He’d received too many death threats and moved his family to the U.S.

Saab seems to have a knack for winning the confidence of people in high places. He liked to vacation in the Caribbean nation of Antigua and Barbuda, flying in on his Gulfstream G280 jet, and in June 2014 he persuaded Gaston Browne, the prime minister, to make him a special economic envoy to Venezuela, complete with Antiguan citizenship and a passport. Then he asked Browne for approval to build a factory in Antigua to make housing panels. “The idea would be to export to Venezuela,” says Browne. About two and a half years ago, the prime minister sent people, including one of his ministers, to Venezuela for a tour of a factory Saab said he owned. They were impressed with what they saw, though the Antiguan factory was never built, Browne says. “I have to admit that Alex has become a friend. He is very genuine, a good successful businessman.”

After reports surfaced of Saab’s dealings with the Maduro government, Browne summoned him to a cabinet meeting to discuss the allegations. “He said it was all political, that they were going after him for doing business with Venezuela,” says Browne. “He said he was innocent of the allegations.”

Saab, for his part, has sent his lawyers after journalists who’ve published allegations of illegality. Last year, Saab sued Univision Communications Inc., the Spanish-language television network, twice in state court in Miami for defamation over stories about his businesses. Saab dropped one of the suits after Univision denied the allegations and sought to depose him. The other lawsuit is pending, awaiting Saab’s response to Univision’s motion to dismiss. In 2017, Saab sued the Venezuelan investigative news site Armando.info in Caracas for defamation over reports that he was a front for Maduro and involved in corrupt food contracts, leading four journalists to move to Colombia for fear of being banned from reporting and, possibly, jailed in Venezuela. That case is pending.

No comments:

Post a Comment