To Correct the whistleblowers complaint: There was no shortage of equipment! Cuomo wanted 40,000 ventilators and the Trump administration provided him with so many he could give the thousands of surplus to other states. And as it turned out ventilators were not the benefit first thought.

The CDC Lost Control Of The Coronavirus Pandemic. Then The Agency Disappeared.

The world’s premier health agency pushed a flawed coronavirus containment strategy — until it disappeared from public view one day before the outbreak was declared a pandemic.

On January 17, the world’s most trusted public health agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, announced it was screening travelers from Wuhan, China, because of a new infectious respiratory illness striking that city.

It was the CDC’s first public briefing on the outbreak, coming as China reported 45 cases of the illness and two deaths linked to a seafood and meat market in Wuhan. Chinese health officials had not yet confirmed that the new illness was transmitted from person to person. But there was reason to believe that it might be: four days earlier, officials in Thailand confirmed their first case, a traveler from Wuhan who had not visited the seafood market.

“Based on the information that CDC has today, we believe the current risk from this virus to the general public is low,” said Nancy Messonnier, the CDC’s director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Messonnier, 54, was a veteran of the CDC’s renowned Epidemiological Intelligence Service, where she had risen through the ranks during the national responses to the anthrax attacks and the previous decade’s swine flu pandemic to eventually head the agency’s vaccines center.

Most of the novel coronavirus’s infections apparently went “from animals to people,” she explained, and human transmission was “limited.”

There were many reasons why the information the CDC had on January 17 was wrong. It was wrong because China’s leaders withheld what they already knew about the virus from the World Health Organization. It was wrong, perhaps, because Trump administration officials had cut CDC staffers in Beijing who might have reported the truth directly from China. And it was wrong because past coronavirus outbreaks provided a false guide to an illness new to humanity.

That last reason — a fateful misjudgment of the basic biology of the virus — drove a flawed strategy to contain the outbreak. In 17 press briefings from January to March, the agency pushed the idea that if travelers, first from Wuhan and then from China, were quickly identified, traced, and isolated, it could “slow and reduce” the spread of the virus on US soil. Believing people without symptoms didn't spread the virus, the agency limited testing, discouraged masking, and left the country blinded by a faulty COVID-19 test.

Then, when the containment strategy's failure became undeniable, just one day before the WHO declared the outbreak a pandemic — the CDC disappeared from public view.

“When the outbreak started, we had an aggressive tracing program, but unfortunately, as the cases rose, it went beyond the capacity,” CDC Director Robert Redfield later testified to Congress.

“We lost the containment edge.”

More than 120,000 US deaths and counting later, public health experts disagree whether the CDC — which only resumed its briefings on the coronavirus in June after its three-month vanishing act — could have ever contained SARS-CoV-2. Everyone agrees, though, that the US response has been a disaster across the federal government, with the CDC the most visible face of failure.

“We certainly could have done enormously better than we did,” former CDC director Tom Frieden told BuzzFeed News.

Could the US have stopped the outbreak completely, like Taiwan and New Zealand have done?

“Probably not,” said Frieden. “Could we be Germany, with way, way fewer cases and deaths and less economic dislocation? Absolutely.”

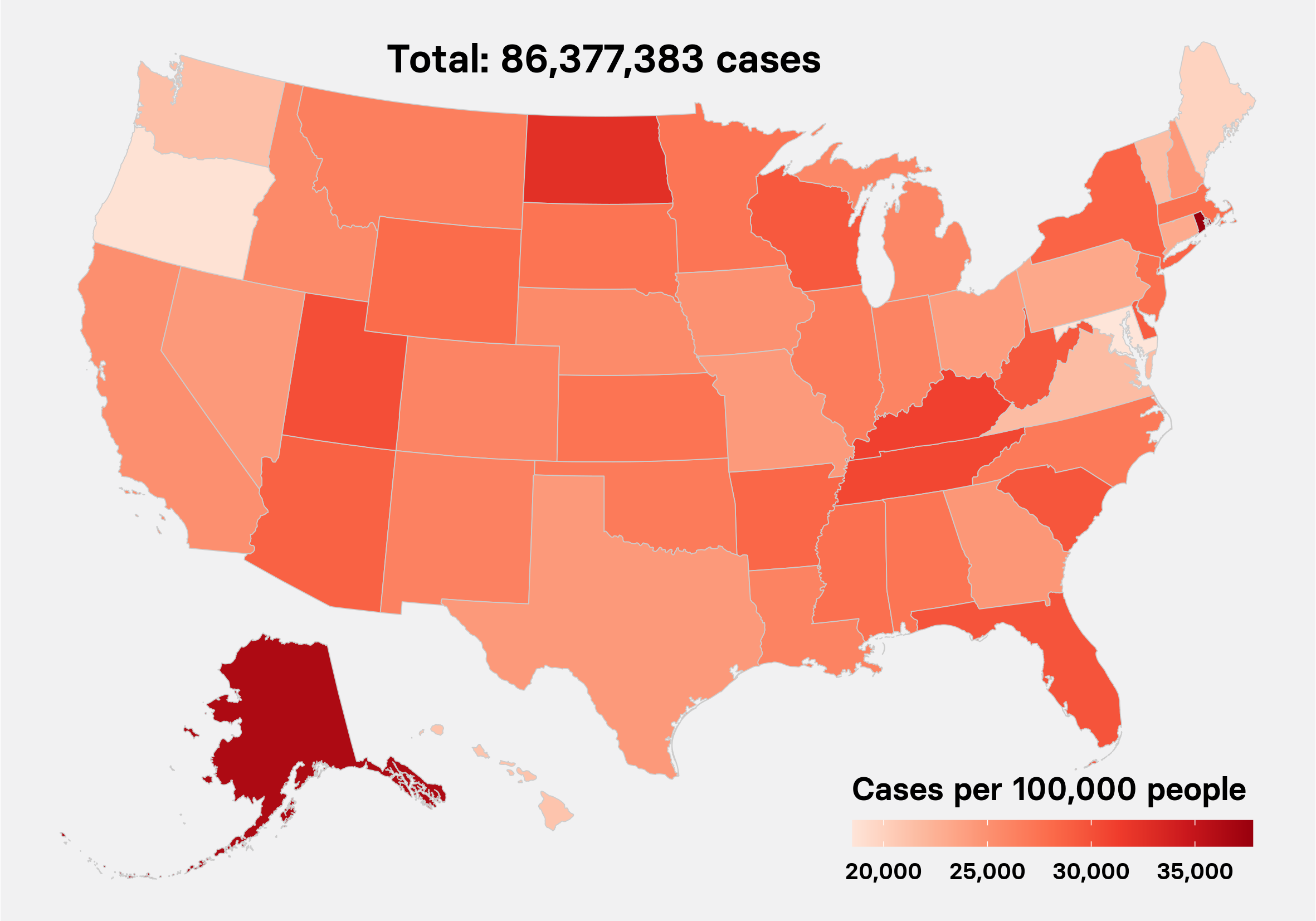

Peter Aldhous / BuzzFeed News

A fatal misunderstanding about the new virus

At that first CDC coronavirus briefing, Messonnier explained what two other coronaviruses, MERS and SARS, could tell us about how to contain the mysterious new virus. And she described the crux of their containment plan: stopping the disease from entering the US by screening for travelers with a fever and a cough, testing them, and putting sick people in isolation.

“We know from investigation of those two viruses that they are more likely to spread when somebody is more contagious,” she said. “Asymptomatic people can spread, but at a much lower rate.”

SARS was a novel coronavirus whose outbreak in 2002 and 2003 killed 774 people, largely travelers and hospital personnel. It was most contagious when someone was severely ill, making quarantines very effective because by the time someone was most contagious, they were usually already confined to a hospital bed. MERS, which has killed at least 845 people since 2012, is likewise most often transmitted from terribly ill patients.

Samuel Corum / Getty Images

Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, speaks during a press conference at the Department of Health and Human Services on Jan. 28 in Washington, DC.

SARS-CoV-2 is entirely different. We now know that COVID-19 patients have the heaviest viral load — and appear most infectious — at the onset of symptoms, not at the end. People who haven’t yet developed any symptoms, and therefore wouldn’t show up in the CDC’s temperature checks, are responsible for more than 40% of the virus’s spread. And only about 45% of cases early in an infection will develop a fever.

In its first briefing, CDC officials acknowledged they still knew very little about the new virus. “CDC will adjust its screening and response procedures appropriately,” said the CDC’s Marty Cetron, director of the Global Migration and Quarantine Division.

Three days later, China confirmed the virus spread from person to person. Within a week, Chinese officials took the unprecedented move of quarantining Wuhan, a city of 11 million people, sending a clear message that the illness could readily spread outside the hospital setting.

Nevertheless, the CDC stuck to its screening plan.

“We are looking for returning travelers who have fever, cough, and respiratory symptoms,” said Messonnier at the agency’s next briefing on January 23. At the following briefing, on January 27, she reiterated the core assumption of the agency’s screening strategy: “We at CDC don’t have any clear evidence of patients being infectious before symptom onset.”

We now know that the coronavirus was likely already spreading on US soil by this time, with at least four lines of evidence supporting that conclusion. There is the case of a Northern California woman who became sick on January 31 and died within a week. And there is genetic evidence: The slow but steady mutation rate of the novel coronavirus, amounting to a few tiny changes every month, serves as a kind of footprint to track its spread. Scientists currently believe that trail points to the virus’s spread starting in November in China and arriving in Washington state in January, spreading through undetected, asymptomatic cases.

On January 30, with 7,800 known cases in 22 countries, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. The same day, the US announced the first case of person-to-person transmission of the virus in the country; the husband of a Chicago woman who had acquired the illness in China.

The next day, Health and Human Service Secretary Alex Azar announced the outbreak was a national public health emergency, and the White House declared a ban on all foreign travelers from China.

China typically sent 14,000 air passengers a day into the US. The order allowed the quarantine of anyone exposed to the virus, and both Redfield and Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, cited the risk of asymptomatic transmission to justify the action.

Alex Wong / Getty Images

Redfield (top left) and Fauci (top right)

Among public health experts, the travel ban was divisive. Some called it both an overreaction and too late, while others have said that such restrictions applied worldwide delayed the outbreak of the virus from China until mid-February.

The real problem was that the travel bans by themselves were a Band-Aid on a dam about to burst, only helpful when paired with public health agencies performing widespread testing and isolating infected patients — both with and without symptoms.

That didn’t happen. California Department of Public Health officials would later complain in a CDC Monthly Morbidity and Mortality Report that the travel restrictions and screening were a distraction and a drain on its resources. “Monitoring travelers was labor-intensive and limited by incomplete information, volume of travelers, and potential for asymptomatic transmission,” said the report. “Despite intensive effort, the traveler screening system did not effectively prevent introduction of COVID-19 into California.”

The real problem was that the travel bans by themselves were a Band-Aid on a dam about to burst.

At a January 31 CDC briefing, Messonnier announced that 195 passengers brought back from Wuhan would be involuntarily held for 14 days at a California air base, the first time in over 50 years that the agency had issued a quarantine order. “We are preparing as if this were the next pandemic, but we are hopeful still that this is not and will not be the case,” she said.

Meissonier’s “next pandemic” statement should have triggered action across the federal government, Frieden, the former CDC director, told BuzzFeed News.

“That's the point at which Iceland and Korea and Germany and a bunch of other countries got the private sector commercial laboratories into scaling up test production, ventilator production, respirators, protective equipment production,” he said.

But that didn’t happen. The next two months would make this failure clear.

No comments:

Post a Comment