Hezbollah’s historical repression of Lebanese neutrality may be coming to an end

The patriarch of Lebanon’s Maronite Church Beshara Al-Rai joined a growing roster of Lebanese leaders who think that the main culprit behind the country’s free-falling economy is Hezbollah and its endless wars.

In a visit to President Michel Aoun, Al-Rai called for restoring regional neutrality, a policy the country used in the past, during which Lebanon saw its “golden years” between 1949 and 1969. Al-Rai also said that national defense should be the job of the Lebanese Army alone.

In a follow-up statement, Al-Rai said that Lebanon used to be “the hospital of the Arabs, the hotel of the Arabs, the tourism of the Arabs,” and that it was Lebanon’s neutrality that allowed it to play such roles.

Lebanese Maronite Patriarch Bechara Boutros Al-Rai speaks after meeting with Lebanon's President Michel Aoun at the presidential palace in Baabda, Lebanon July 15, 2020. (Reuters)

“But when we joined alliances and [militias] and military engagements, we became completely isolated from the Arabs and the West, and we became alone, like a ship in a stormy sea.” The patriarch concluded that “neutrality is the source of national unity and stability, which leads to [economic] growth and prosperity.”

Hezbollah has repressed the debate over its arms and Lebanese neutrality ever since it lost its raison d’être when Israel withdrew from southern Lebanon in 2000. At first, the pro-Iranian militia tried to continue warring with Israel over a tiny strip of land known as Shebaa Farms whose ownership is claimed by Syria. But the narrative of “liberating the Shebaa Farms” never gained traction.

Realizing that Hezbollah had become an obstacle to economic growth, late Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic al-Hariri held rounds of talks with its chief Hassan Nasrallah. Al-Hariri offered Hezbollah a face-saving exit strategy that would have seen the militia transformed into a political group.

The late Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, left, talks with Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, right, during an official ceremony on May 25, 2001 in Beirut. (File photo: AP)

When Hezbollah refused, Al-Hariri lobbied Arab and world capitals. The UN passed Security Council resolution 1559, which called for Hezbollah’s disarmament. Months later, Hariri was assassinated, and a UN special tribunal indicted Hezbollah operatives for the killing.

Al-Hariri’s death, however, did not end calls for Hezbollah’s disarmament, but only intensified them. A coalition of pro-Hariri Sunnis, Maronite Christians under Aoun and his rival Samir Geagea, and Druze under Walid Jumblatt, coalesced around Resolution1559, forcing Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to withdraw his forces from Lebanon, 29 years after having entered it.

Hezbollah, for its part, laid low, and pretended to join in the national unity. In reality, the militia lurked around waiting to break its opponent coalition.

Applying carrots and sticks, Hezbollah lured Aoun away and later helped make him president, while assassinations continued to take down national anti-Hezbollah figures. The party tried to renew its war credentials by starting what it called a defensively preemptive war with Israel in 2006, which resulted in so much destruction that, instead of winning regional and national support, Hezbollah almost lost its Shia base.

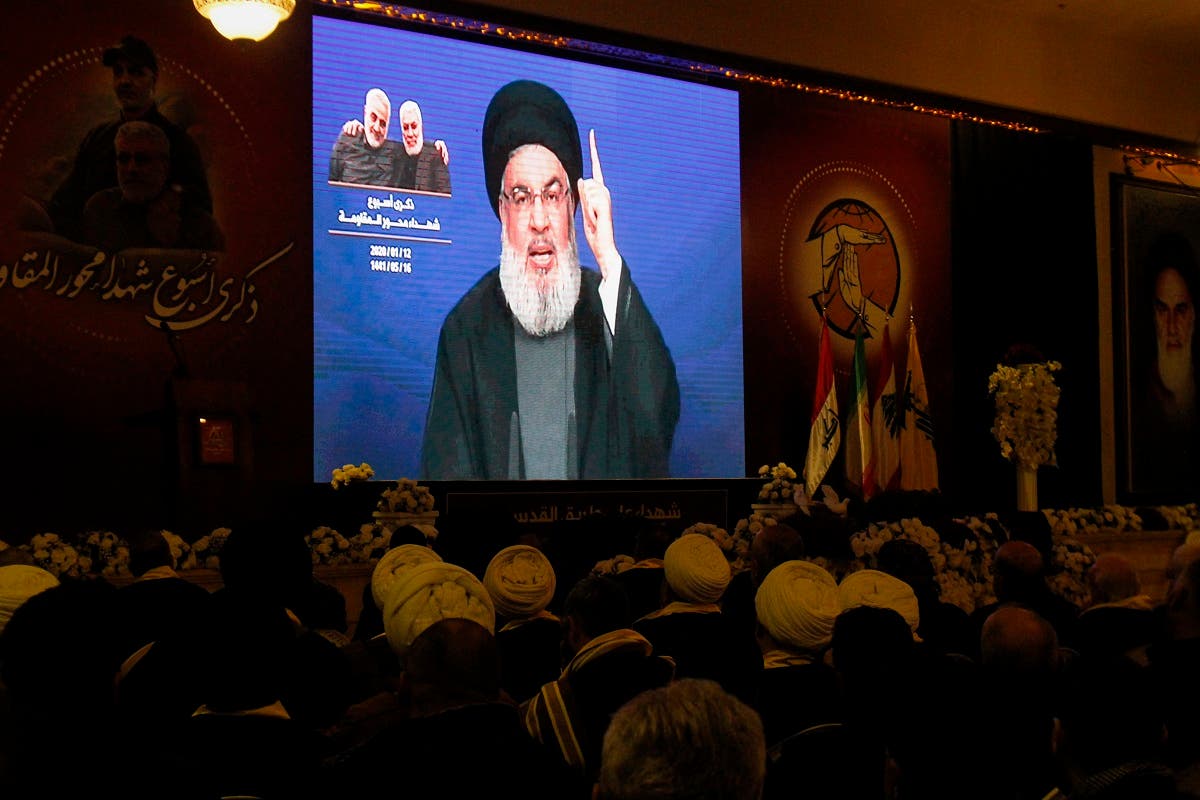

Hezbollah supporters watch as the group's leader Hasan Nasrallah delivers a speech on a screen in the southern Lebanese city of Nabatieh on January 12, 2020. (AFP)

Again, the coalition for disarming Hezbollah came to the rescue, holding indirect negotiations with Israel through the UN to end the war, and soliciting reconstruction money from friends of Lebanon. Gulf capitals proved especially generous in preventing a Lebanese economic collapse. Lebanon was set to implement Security Council resolution 1701, which Hezbollah had agreed to, a resolution that reaffirmed 1559 and called for UN-mediated talks with Israel and Syria to end border disputes and demarcate the borders.

But like always, Hezbollah reneged on what it had agreed to. Hence, with its majority, the coalition to disarm Hezbollah went for one last gasp: It ordered the army to dismantle the militia’s telecom network, perhaps as a prelude to disbanding the militia.

Hezbollah responded with brute force, sending its fighters to invade neighborhoods and villages, and killing many.

The terms to end Hezbollah’s mini civil war in 2008 stipulated, yet again, neutrality. Michel Suleiman, who was elected president by consensus, summoned the oligarchs and Hezbollah to agree on neutrality, and encoded the agreement in the Declaration of Baabda 2012. Next, Hezbollah went after Suleiman, slandering him until his term ended.

Lebanon's President Michel Suleiman speaks during the third Lebanon Economic Forum in Beirut March 8, 2014. (File photo: Reuters)

After Suleiman, Hezbollah was determined to install a loyalist president who would never call for disarmament or neutrality. Aoun obliged. But by controlling all levers of power, the world realized that Lebanon was now in Hezbollah’s pocket. The country thus lost its international friends. It’s economy started its decline.

A free-falling economy convinced Al-Rai, who had been on the fence, to join the chorus calling for Hezbollah’s disarmament and Lebanese neutrality. Al-Rai’s position surprised the pro-Iranian militia, whose early reaction included defaming the patriarch.

But the head of the Maronite Church is a heavyweight in Lebanese politics, and his call for neutrality started snowballing.

Hezbollah is on the back foot again, and will probably revert to its usual playbook: Try to divide and conquer its opponents with violence and promises of senior state jobs. Whether the party succeeds in repressing calls for its disarmament, like it did in the past, is anybody’s guess.

The only difference today is that the party will have to play its game unlike anytime before: Against the background of an unfolding Lebanese famine.

________________

Hussain Abdul-Hussain is an Iraqi-Lebanese columnist and writer. He is the Washington bureau chief of Kuwaiti daily al-Rai and a former visiting fellow at Chatham House in London. He tweets @hahussain.

Last Update: Wednesday, 22 July 2020 KSA 21:57 - GMT 18:57

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not reflect Al Arabiya English's point-of-view.

No comments:

Post a Comment