The city of Berkeley has long been a liberal bastion in a region already known for its lefty politics. And yet, despite its status as a progressive university town, Berkeley is at the forefront of

one prong of the war against vaccines. Last night’s city council meeting here revealed the hippie side of the anti-vaxxer movement.

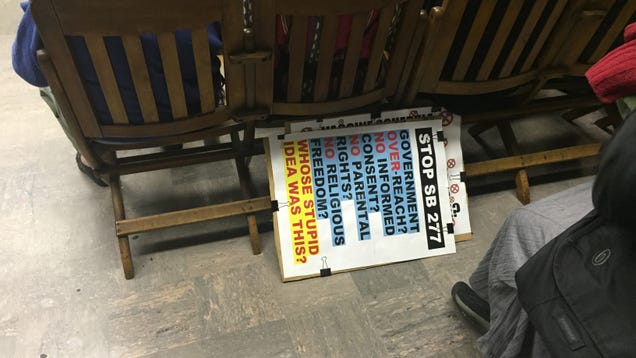

The standing-room-only crowd at the meeting was there to protest what was, in some ways, the least essential item on the agenda. One council member had proposed sending a letter to the California state legislature in support of SB 277, a proposed bill that would get rid of the state’s personal belief exemptions for vaccines, while keeping medical exemptions intact.

Today, the state Senate Health Committee approved the bill, which needs to pass the Senate before going to the Assembly. It still has a long way to go. But last night, outraged protesters pushed for Berkeley to refuse support for the bill, arguing that Californians should have the right to refuse vaccines for “personal beliefs.”

In effort to mollify the crowd, Berkeley mayor Tom Bates had this to say about the importance of a city council’s letter: “Most people really don’t think it’s significant.” But oh, it is! The city’s resolution may be many steps removed from the legislative process, but it’s directly related to injecting things into the bodies of your children. This isn’t like sewage fees or solar energy mandates, to pick a few other items from last night’s agenda. It’s a visceral, divisive issue.

As Berkeley resident, I found the city council meeting both exasperating and enlightening. There is something slightly farcical about so much hoopla over a city council resolution to send a letter in support of a proposed, but I came to realize that vaccine exemption debates should happen in the local community. I just hope they don’t all go badly as they did in Berkeley.

Who calls the shots?

In over an hour of public comment, there were, by my count, 6 people lined up to speak in support of SB 227 and about 30 people against. The most prominent speakers in support of the bill were a trio of young University of California, San Francisco medical students, dressed in white coats and carrying signs on neon paper. I agreed with what they said, but man, they looked like kids lecturing at a science fair.

The opponents of the bill included many mothers and grandmothers who were old hands at staging an event at city council meetings. They staked out seats in front of the TV cameras. They lined up allies to stand in line and cede their time to designated speakers.

“I like vaccines but I opposed SB 277” — Opponents of SB 227 see it as a matter of personal freedom. “It is a human right,” said Leslie Hewitt, a chiropractor in California. The crux of the argument is that why should politicians make all-encompassing decisions about their children’s health, rather than parents and doctors on an individual basis?

“There is no crisis in vaccination rates” — California child care facilities have an up-to-date vaccination rate of

89.4 percent. Personal belief exemptions account for 2.67 percent of the gap. True, the overall percentages are small, but non-vaccination is not evenly distributed. Berkeley’s is at 81.45 percent. In particular, the non-vaccination is clustered around certain schools. At the private Berkeley Rose School,

78 percent of the kids enrolled in child care had personal belief exemptions for vaccines. (By the way, this school is a few blocks from my apartment.)

“We have corrupt science” — A common refrain was that the number of required vaccine doses has gone up in recent decades, and that the bill itself was open-ended, allowing new vaccines to be added to the schedule. There are over “200 new vaccines in trials,” noted many speakers, pointing the finger at pharmaceutical profits. When one speaker unfavorably compared the U.S. medical system to Cuba’s (because they require fewer vaccines!), I had to sigh and remember I was in Berkeley.

A crisis in the community

I doubt anyone was convinced to reconsider their positions on vaccines last night, but one woman’s comment did strike particular a chord with me. “I love love love living in Berkeley,” she said, “I’ve never lived in a place with such a strong sense of community, which is why I was so shocked to find out that so many people here oppose vaccines.”

This is crux of why the personal choice argument is flawed. Immunization prevents the spread of diseases to protect the most vulnerable people—infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised people who cannot get vaccinated themselves. This is called “herd immunity.” When vaccination is debated in the halls of Sacramento or Washington, D.C., it seems like an abstract point. But at City Hall, you might actually have to face a neighbor whose infant could get measles from your unvaccinated child.

To look at it selfishly, whether someone in San Diego vaccinates their kids matters far less to me than whether the parents in my hypothetical children’s local school vaccinate. We rationally care about the circle of people closest around us. Non-vaccination is a nation-wide problem, yes, but it is a problem whose effects will radiate out first from our local communities.

Eula Biss’s book On Immunity offers an examination of vaccination that seems relevant here. “Herd immunity,” she rightly points out, is terrible phrase, evoking dumb cattle going to slaughter. One particular passage from her book acknowledges many of the concerns I heard from Berkeley parents, but she neatly inverts their argument:

We are justified in feeling threatened by the unlimited expansion of industry, and we are justified in fearing that our interests are secondary to corporate interests. But refusal of vaccination undermines a system that is not actually typical of capitalism. It is a system in which both the burdens and the benefits are shared across the entire population. Vaccination allows us to use the products of capitalism for purposes that are counter to the pressures of capital.

Biss’s argument is a pretty conceptual one, but it appeals, fundamentally, to our moral values (and, while we’re at it, Berkeley’s relatively anti-capitalist tendencies). The impulse to refuse vaccines reflects some of the most cynical and selfish parts of ourselves.

In the end, the Berkeley city council passed the resolution 7-1, on the advice of basically every medical organization. If you had only heard what was being said in the room though, it would have seemed like established interests were once again silencing the voices of people. The opponents are a minority, but a very, very vocal one.

As SB 227 moves forward in the California capitol, proponents of vaccination need to step up to the plate. Discussions about vaccination do need to happen within local communities, not just at state and federal hearings. Rather than appealing to science, we need to appeal to our sense of community.

No comments:

Post a Comment