Questions of cuisine and culture surround Coppola’s new restaurant

November 4, 2016 Updated: November 4, 2016 7:45pm

What is the line between honoring a long-neglected cuisine and misrepresenting it? The Bay Area’s best known celebrity winemaker is finding out.

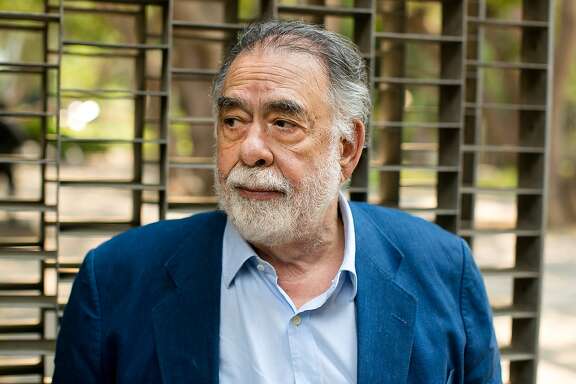

Saturday is opening day for filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola’s Werowocomoco in Geyserville, perhaps the Bay Area’s first American Indian restaurant. It is located in Coppola’s year-old Virginia Dare Winery and named after a political capital of the Algonquian tribes who lived in Virginia when British colonists arrived.

Werowocomoco appears at a time when publications like the New York Times and the Atlantic are profiling American Indian chefs, yet only a handful of restaurants serving indigenous North American cuisines are operating across the country.

It is also a moment rife with conversations about the treatment of American Indians. Furor over the offensiveness of the Cleveland Indians’ Chief Wahoo logo crescendoed alongside the team’s appearance in the World Series. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s fight to block an oil pipeline being constructed across sacred lands in North Dakota has migrated to Facebook, where hundreds of thousands of Americans are clicking their support.

Coppola’s vision of a Native American restaurant includes painted animal skins stretched across the restaurant’s raw wood walls and a bar framed in dramatic black-and-white patterns. Coppola has become Werowocomoco’s chef as well, and one preliminary menu lists bison burgers with acorn-flour buns, roasted “prairie chicken,” and frybread tacos topped with wild rice and dried cranberries.

Early responses to the restaurant, however, have put its owner on the defensive.

Several articles about the restaurant have looked askance at it naming itself after a Virginia site rather than one reflective of Northern California’s many tribes. According to Coppola, the Pamunkey Tribe in Virginia granted him permission to use the name Werowocomoco. The chief of the Pamunkey Tribe did not respond to an interview request.

Members of other Virginia tribes, though, have taken to social media, calling the restaurant an “outrage” and a “disgrace.”

One of the critical commenters, Washakie Fortune, is a member of the Rappahannock Tribe, one of the 30 tribes that have made up the Powhatan Confederation historically connected to Werowocomoco. “One tribe does not speak for us all,” Fortune wrote in an email. “Werowocomoco is a sacred meeting spot for Chief Powhatan and other leaders of tribes and the confederation. To name this restaurant after it, and to serve alcohol there, is a disgrace to my people and all others of the Powhatan Confederation.”

Coppola is adamant about his qualifications to operate Werowocomoco. In an article he wrote for The Chronicle’s opinion pages, published Friday, he described the meals he has eaten in Native American homes while planning the restaurant and pointed to a council of advisers who assist him. He promises to donate 5 percent of Werowocomoco’s proceeds to “America’s Native people.”

Opening Werowocomoco has dragged Coppola, willing or not, into an impassioned public discussion taking place around culture and cuisine.

Social media has given diners of color a forum for calling out restaurants and publications on how they represent the food of their cultural heritage. Several months ago, for instance, Bon Appetit magazine took down a video of a white chef telling viewers “how to eat pho” after scorn flooded Twitter and Facebook. The term “Columbusing,” referring to white chefs or writers’ self-professed attempts to “elevate” or “improve” dishes from other cuisines, pops up more and more.

In June, East Bay Express restaurant critic Luke Tsai wrote a feature about this conversation, titled “Cooking Other People’s Food.” Tsai argued that diners, media and cooks alike need to be more conscious of when and why they reward chefs for specializing in cuisines they didn’t grow up with. It didn’t bother him, for instance, that at the East Bay restaurants Comal and the Ramen Shop, white and Filipino American chefs are cooking Mexican and Japanese food. What Tsai pointed out was the media attention, and financial investment, that both restaurants have attracted while businesses run by Mexican and Japanese American cooks get ignored.

“If you’re a white chef who wants to open a Thai restaurant, I think that’s fine, but you need to be able and willing to have that conversation,” Tsai said.

The other question Werowocomoco is tackling: What should Native American cuisine be? Does a bison burger represent Native American food, or is it cultural appropriation? And should a native-inspired restaurant even serve frybread? It’s a dish that some native chefs refuse to serve because it represents poverty and ill health, while others spotlight it as the most comforting of home-style cooking.

Photo: Virginia Dare Winery

The interior of Werowocomoco, Francis Ford Coppola's new restaurant in Geyserville

Lois Frank, a member of the Kiowa nation and a culinary historian and chef in Santa Fe, N.M., argues that Native American cuisine is dynamic and multifaceted. Expecting indigenous chefs to limit themselves to foraged and wild ingredients is folly, she said. Not only did tribal trade routes stretch across the continent long before Europeans arrived, indigenous cooks quickly took to foods the colonists introduced to the continent.

Others have similar sentiments when it comes to seeing the cuisine evolve. “If Francis wants to help push Native American cuisine to the fore, I’m all for it,” Loretta Barrett Oden said in an email. Oden is an Oklahoma City chef, food historian and member of the Potawatomi Tribe. She is also on Coppola’s council of advisers for Werowocomoco. To her, more upsetting than an Italian American winemaker opening an American Indian restaurant is the fact that American Indian-owned casinos do not offer native cuisine.

“If the choice is finding new collaborations to advance traditions of native foods, traditional ingredients, cooking and the accurate stories that accompany each of these elements of indigenous culture so they can flourish in the future, then I can’t imagine a collaboration to do so more productively — and maybe even constructively provocative — than one supported by Francis Ford Coppola,” Oden wrote.

What’s more important, argued Frank, is that any restaurant serving Native American cuisine work in partnership with cooks, suppliers and communities. “My philosophy would be to bring in Native consultants and as many Native cooks and collaborate,” she said. “So you’re not speaking for someone else.”

Jonathan Kauffman is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: jkauffman@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @jonkauffman

No comments:

Post a Comment