Key constituents only supported 2016 legislation because of its "true conscious objection and opt out." Amended law, approved last fall, infringes on freedom of religion and speech, lawsuit claims.

California doctors who object to assisted suicide are fighting an amended state law that implicates them in their patients' intentional deaths.

They are suing California officials, including Attorney General Rob Bonta, Department of Public Health Director Tomas Aragon, and Medical Board members to block SB 380, which made it easier for patients to commit suicide under the End of Life Options Act that took effect in 2016.

The original law issued a broad exemption for healthcare providers, granting them a liability shield for "refusing to inform" patients about their right to physician-assisted suicide and "not referring" patients to physicians who will assist in their suicides.

The amended law removed it, leaving providers vulnerable to "civil, criminal, administrative, disciplinary, employment, credentialing, professional discipline, contractual liability, or medical staff action, sanction, or penalty or other liability."

Conscientious objectors are suffering irreparable harm to their free exercise of religion and speech, the suit claims, seeking an injunction and declaration that the law is unconstitutional under any application. California is infringing on their "right not to speak the State's message on the subject of assisted suicide."

The Alliance Defending Freedom is representing the Christian Medical and Dental Associations, which claims 90% of its 16,000 members would quit medicine rather than be subject to such laws, and its member Dr. Leslee Cochrane, executive director of the nonprofit Hospice of the Valleys, who said he'd either quit or leave California.

Signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom last fall, SB 380 claims that "participating" in assisted suicide is "voluntary" but narrowly defines the former, depriving physicians of legal protection for refusal to take steps that authorize intentional killing.

They must document a patient's request to die in that individual's medical record, which satisfies the first of two required "oral requests" for a patient to obtain a prescription for lethal drugs. Physicians also must transfer those records to a second physician upon the patient's request.

Participating also excludes "[d]iagnosing whether a patient has a terminal disease, informing the patient of the medical prognosis, or determining whether a patient has the capacity to make decisions," and informing a patient about assisted suicide options.

This language concerned two legislative committees reviewing the bill.

The Senate Health Committee's analysis noted the California Medical Association only supported the 2016 legislation because of its "true conscious objection and opt out" provision. The California Hospital Association flatly said it would oppose SB 380 with the narrow definition of "participating."

The Senate Judiciary Committee's analysis said the bill raises "constitutional questions with respect to freedom of speech and the free exercise of religion," given that physicians face "exposure to liability" for not "affirmatively facilitating" a patient's rights under the law.

The Assembly Judiciary Committee (AJC) analysis a few months later left out that concern, possibly because the bill had been amended by then. The lawsuit claims the revision did not change the exceptions to "participating" but organized them differently.

Continuing a pattern going back to assisted suicide legislation in the 1990s, advocates for disabled people opposed the California bill.

Disability Rights California objected to shortening the 15-day waiting period under the original law to 48 hours and removal of the "final attestation" by the patient. The latter "puts patient autonomy at risk, opening the door to abuse by greedy heirs or abusive caregivers," argued the DRC.

The Senate floor analysis, the last hurdle before passage, records comments from the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, which says its community is "full of individuals who have been misdiagnosed as terminally ill."

The bill removes protections such as more and better-trained medical professionals to "judge a patient's prognosis and assess their decision-making capacity," and it includes "extraordinarily little monitoring, data, and investigation of abuse," even less so than similar laws in Oregon and Washington, the group said.

Terminally ill patients "can have very dramatic changes in disposition once their pain is controlled," according to the lawsuit, citing individual plaintiff Cochrane's hospice experience.

Referring to the shortened waiting period, he said patients in severe pain can suffer "mental, emotional, and spiritual exhaustion" for more than two days at a time that "leaves them vulnerable to being easily manipulated by family members" against their own wishes. This happened to at least one patient with "questionable mental capacity," Cochrane said.

The California League of United Latin American Citizens called the legislation a threat to Latinos because it worsens racial inequality in healthcare. This is "just an opportunity for commodity-based, profit-driven health systems to cop out of care by providing the ever-cheap 'option to die,'" according to its comments recorded in the Senate floor analysis.

The California law finds no support in the Supreme Court's Roe v. Wade decision nationalizing abortion rights, which cited an American Medical Association (AMA) resolution against compelling doctors to perform acts that violate their "good medical judgment" or "personally-held moral principles," the suit says.

Two decades later, the high court unanimously rejected physician-assisted suicide as a "fundamental right" bcause it is "fundamentally incompatible with the physician's role as healer." The suit notes that the AMA's 2017 statement on assisted suicide, its most recent, goes even further, saying the practice is "difficult or impossible to control" and poses "serious societal risks."

The Affordable Care Act also prohibits states and federally funded healthcare providers from discriminating against individuals and entities that refuse to provide any product or service "furnished for the purpose" of even indirectly causing "the death of any individual," the suit says.

Yet the amended law treats physicians participating in assisted suicide more favorably than those who refuse, as the former cannot be subject to "a complaint or report of unprofessional or dishonest conduct" solely on the basis of their decision to help patients kill themselves, the lawsuit says.

On Monday, a former business partner of Hunter Biden named Devon Archer has been sentenced to over a year in prison for his involvement in a scheme to defraud a Native American tribe of over $60 billion in bonds. Not surprisingly, all three evening newscasts completely ignored this news of the President’s son’s business partner going to federal prison.

On Monday, a former business partner of Hunter Biden named Devon Archer has been sentenced to over a year in prison for his involvement in a scheme to defraud a Native American tribe of over $60 billion in bonds. Not surprisingly, all three evening newscasts completely ignored this news of the President’s son’s business partner going to federal prison.

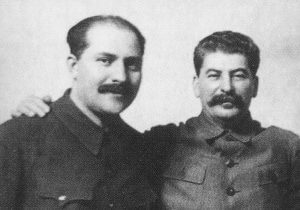

In reading about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I’ve come across sources that mention Russia’s economy, Putin’s historical revisionism, Zelenskyy’s background as an actor, Russian military tactics, oil pipelines, Finland’s military might, and the complex history between Russia and Ukraine. But I am amazed that there is one name that I have not seen mentioned anywhere: Lazar Kaganovich.

In reading about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I’ve come across sources that mention Russia’s economy, Putin’s historical revisionism, Zelenskyy’s background as an actor, Russian military tactics, oil pipelines, Finland’s military might, and the complex history between Russia and Ukraine. But I am amazed that there is one name that I have not seen mentioned anywhere: Lazar Kaganovich. Ten years ago, I befriended a woman who moved to Tennessee from Ukraine with her junior high school daughter (who was in my daughter’s class – they became best friends). I mentioned that I knew Kaganovich’s grandson, and my friend was shocked, but her daughter had no idea who he was. She went to school in Ukraine until age 14, and had never heard of Kaganovich, who was responsible for the deaths of many in her family. I wonder how many Ukrainians are unaware of this period of their history? It was 90 years ago, so no one alive was there at the time. But is it possible that no one remembers it at all?

Ten years ago, I befriended a woman who moved to Tennessee from Ukraine with her junior high school daughter (who was in my daughter’s class – they became best friends). I mentioned that I knew Kaganovich’s grandson, and my friend was shocked, but her daughter had no idea who he was. She went to school in Ukraine until age 14, and had never heard of Kaganovich, who was responsible for the deaths of many in her family. I wonder how many Ukrainians are unaware of this period of their history? It was 90 years ago, so no one alive was there at the time. But is it possible that no one remembers it at all? Imagine if 70 years ago, Germany had killed millions of Jews (which, of course, they did). And then imagine that Germany invaded Israel today. Can you imagine the press coverage? Every Western news channel would run endless loops of Hitler speeches and Jews in concentration camps. As they should.

Imagine if 70 years ago, Germany had killed millions of Jews (which, of course, they did). And then imagine that Germany invaded Israel today. Can you imagine the press coverage? Every Western news channel would run endless loops of Hitler speeches and Jews in concentration camps. As they should. Putin may be unpredictable. But Russia is not. They even cheat in figure skating, for Pete’s sake. Even when everybody knows they’re cheating, and they’ve already been suspended. They lie, and they cheat. After all, it’s Russia we’re talking about here, right? Even Jimmy Carter figured this out. Eventually.

Putin may be unpredictable. But Russia is not. They even cheat in figure skating, for Pete’s sake. Even when everybody knows they’re cheating, and they’ve already been suspended. They lie, and they cheat. After all, it’s Russia we’re talking about here, right? Even Jimmy Carter figured this out. Eventually. Many tyrants have openly acknowledged that you can’t control a country’s future without first controlling its history. Islamists seek to control countries by destroying any ancient artifacts which don’t fit with Islam. Putin just gave a speech claiming that his Russian ‘peacekeeping forces’ were merely attempting to free Ukraine from Nazi control (Ukraine’s Prime Minister is Jewish). American leftists have been tearing down statues and renaming schools on a wholesale level. All for the same reason.

Many tyrants have openly acknowledged that you can’t control a country’s future without first controlling its history. Islamists seek to control countries by destroying any ancient artifacts which don’t fit with Islam. Putin just gave a speech claiming that his Russian ‘peacekeeping forces’ were merely attempting to free Ukraine from Nazi control (Ukraine’s Prime Minister is Jewish). American leftists have been tearing down statues and renaming schools on a wholesale level. All for the same reason.