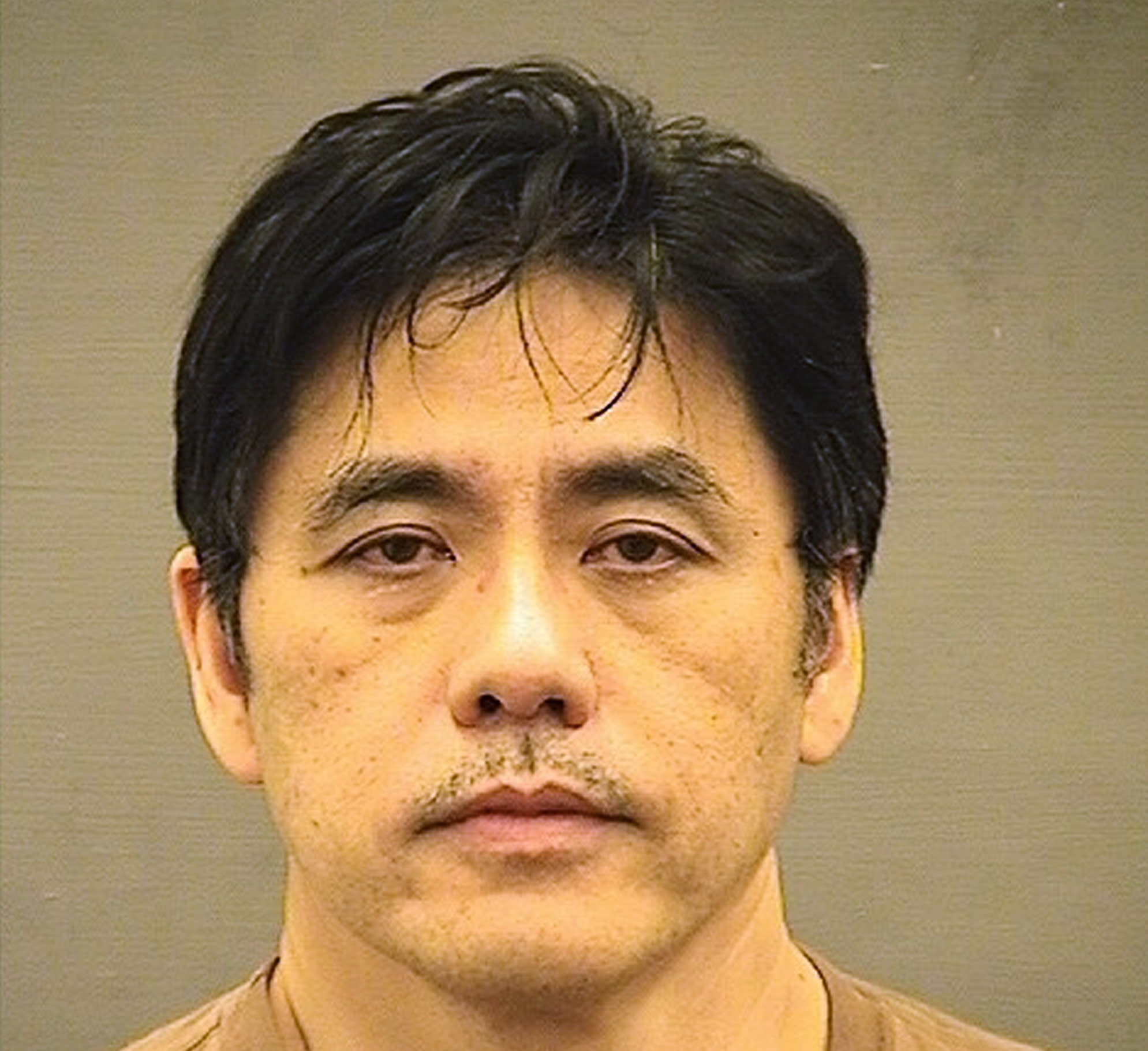

Ex-CIA Officer Sentenced to 19 Years in Chinese Espionage Conspiracy

ALEXANDRIA, Va. — A former CIA officer was sentenced Friday to 19 years in prison for conspiring to deliver classified information to China in a case that touched on the mysterious unraveling of the agency’s informant network in China but did little to solve it.

The former officer, Jerry Chun Shing Lee, 55, pleaded guilty in May to conspiring with Chinese intelligence agents starting in 2010, after he left the agency. Prosecutors detailed a long financial paper trail that they said showed that Lee received more than $840,000 for his work.

Lee, an Army veteran, worked for the CIA from 1994 to 2007, including in China. After he resigned, he formed a tobacco company in Hong Kong with an associate who had ties to the Chinese intelligence community. Lee then began meeting with agents from China’s Ministry of State Security, who assigned him tasks he admitted to taking on and offered to “take care of him for life.”

While working in Hong Kong in 2010, Lee reapplied for employment with the CIA but misled U.S. officials repeatedly in interviews about his dealings with Chinese intelligence officers and the source of his income.

Around the time Lee began speaking to Chinese agents, the CIA was rocked by major setbacks in China as its once-robust espionage network there began to fall apart. Between 2010 and 2012, dozens of CIA informants in China disappeared, either jailed or killed, embroiling the agency in an internal debate about how Chinese intelligence officers had identified the informants. Many within the agency came to believe that a mole had exposed U.S. informants, and Lee became a main suspect.

But FBI agents who investigated whether he was the culprit passed on an opportunity to arrest him in the United States in 2013, allowing him to travel back to Hong Kong even after finding classified information in his luggage. FBI agents had also covertly entered a hotel room Lee occupied in 2012, finding handwritten notes detailing the names and numbers of at least eight CIA sources that he had handled in his capacity as a case officer.

The investigators apparently decided that by continuing to quietly monitor Lee, they might glean more clues about the disappearing CIA informants in China. But even after his arrest in 2018 on the same charge the CIA was prepared to bring in 2013, they were unable to determine whether Lee was involved in the disclosures to Chinese intelligence operatives.

Because of Lee’s plea agreement, in which he admitted to one count of possessing information classified as secret — a lower level than top secret — prosecutors asked for a relatively lighter sentence of roughly 22 to 27 years, rather than life in prison.

But prosecutors argued that even if Lee never turned over information to Chinese intelligence officers, the fact that he shared his knowledge of U.S. intelligence work with Chinese agents alone could have a chilling effect on the CIA’s source-building efforts.

“It makes it difficult to recruit people in the future if they know the CIA isn’t protecting their people,” said Adam L. Small, a federal prosecutor in Northern Virginia, where Lee was charged. “These are people who put their names and lives in his hands.”

The sentence for Lee is the latest in a string of recent cases in which U.S. intelligence workers have been handed lengthy prison terms for espionage connected to China. In announcing Lee’s sentence, Judge T.S. Ellis III said that a hefty sentence was necessary to deter others from jeopardizing U.S. intelligence.

In May, another CIA case officer, Kevin Patrick Mallory was sentenced to 20 years in prison for selling classified documents to a Chinese intelligence officer for $25,000. Ellis, who presided over that case as well, decided that a life sentence for Mallory was excessively harsh even though prosecutors showed he successfully transmitted secret information.

In September, Ron Rockwell Hansen, a former Defense Intelligence Agency officer, received 10 years in prison for attempting to pass along defense secrets.

Lee’s lawyers argued that the largely circumstantial case against him was considerably weaker than others in which defendants were charged with espionage, and that speculating that the unexplained payments he received were compensation for information that harmed CIA operations was “a bridge too far.”

Although Lee pleaded guilty to conspiring with Chinese agents, lawyers on both sides conceded that there was no direct evidence that Lee ever provided any of the classified information in his possession to the Chinese government. The CIA has not shown that the sources listed in Lee’s notes faced retribution or harm, Lee’s lawyers said.

“What the government is describing is their worst possible nightmare,” said Nina J. Ginsberg, one of Lee’s lawyers.

In announcing the sentence, Ellis said he was not convinced that Lee’s interactions with Chinese intelligence officers were benign, and that it is common in espionage cases to never fully uncover the extent of illicit dealings.

While he acknowledged that Lee, a naturalized citizen born in Hong Kong, had done a great deal with his life as an American — four years in the Army, a 13-year career with the CIA — Ellis appeared unmoved.

“That gets erased,” he said, “when you betray your country.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2019 The New York Times Company