Sufi Abdul Hamid, the Black Hitler of Harlem

By Daniel Greenfield —— Bio and Archives--April 14, 2011

American Politics, News, Opinion | Disqus Comments |

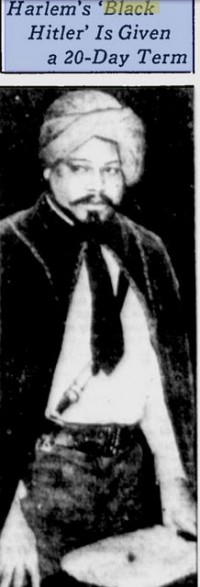

The Black Hitler was a Chicago community organizer who moved to New York. Somewhere along the way he picked up a gold lined cape, a purple turban and a stepladder which he used to give speeches outside of the Jewish stores owned by Harlem’s dwindling Jewish community.

The cape and the turban were sometimes combined with Nazi style military shirt and pants, and jackboots, along with a fez, completing the uniform of a man who is remember today as a pioneering labor leader—but was known back then as the Black Hitler. A dagger thrust through his belt completed the ensemble.

The cape and the turban were sometimes combined with Nazi style military shirt and pants, and jackboots, along with a fez, completing the uniform of a man who is remember today as a pioneering labor leader—but was known back then as the Black Hitler. A dagger thrust through his belt completed the ensemble.

In his stepladder speeches, he declared himself the only man who could stop the Jews, accusing them of spreading filth and disease, and called on his followers to tear out the tongue of any Jew they met. He boasted that he was the “only one fit to carry on the war against the Jews” and vowed an “an open bloody war against the Jews who are much worse than all other whites.” It was speeches like that which earned him the title, ‘Black Hitler’ and intimidated local businesses into hiring workers from his own private labor union.

The Black Hitler styled himself as Sufi Abdul Hamid, when he opened his mosque, he frontloaded his name all the way up to His Holiness Bishop Amiru Al-Mu-Minin Sufi A. Hamid. His press man claimed that he had been born in Egypt beneath the shadow of a pyramid. The truth is that he was born Eugene Brown in Lowell, Massachusetts and in Chicago had called himself Bishop Conshankin, a Buddhist cleric. Like the Nation of Islam, which was finding its feet at around the same time, his theology was a hodgepodge of traditional Islam and whatever else he picked up along the way.

It is unknown what connection Sufi Abdul Hamid had to the burgeoning Nation of Islam, but in the year before he moved to Harlem— Nation of Islam founder Fard Muhammad disappeared, and his successor Elijah Muhammad moved to Chicago after conflicts with the state government and rival NOI leaders. Hamid was probably never part of the Nation of Islam, but he had almost certainly seen it in action, and his New York operation was guided by similar methods.

The year was 1932. In Germany, the actual Hitler was running for president. In New York City, Mayor Jimmy Walker was still reigning as the corrupt but entertaining figurehead of the Tammany Hall Democratic party apparatus, but not for long. In a few months the Seabury Commission’s investigation into the city’s horrifyingly corrupt justice system would send the Tin Pan Alley singing mayor fleeing off to Europe along with his showgirl wife.

The Great Depression had hit New York: The time was ripe for a messiah or a violent explosion. And Sufi Abdul Hamid offered them both

The Great Depression had hit New York’s prosperous commercial and industrial sector like a sledgehammer. The city that never slept had not gone quiet, but it had slowed down. New York’s black population had exploded in its boom days drawn by the lure of jobs, but now that the bust had come the streets of Harlem were full of unemployed men. The time was ripe for a messiah or a violent explosion. And Sufi Abdul Hamid offered them both.

Hamid was not the only one working the streets of Harlem. The Communists in the form of the Young Communist League and the Young Liberators had been there first looking for cannon fodder for the revolution. The Japanese were dreaming of a black army that would serve as their fifth column in the conquest of the United States. Both were to be disappointed. The Black Communist, once commonplace among Harlem intellectuals, would become an endangered species beginning with the Hitler-Stalin pact and ending with the liberal takeover of civil rights. But for now some of those same intellectuals would visit Japan and even endorse its brutal invasion of China.

Marcus Garvey’s UNIA also took Japan’s side. And Imperial Japan’s simultaneous cultivation of Muslims in order to subvert the British Empire, also lead to ties in the US between Japanese officials and the Nation of Islam’s Elijah Muhammad. The Moorish Science Temple, a more explicit fusion of Islam, Asiatic exoticism and Black Nationalism, would eventually be investigated by the FBI for ties to Japan. And the Temple was a probable influence on Hamid’s own Universal Holy Temple of Tranquility. The People’s Voice, a left wing black newspaper, would even claim that Hamid’s temple had been partly funded by Japan.

But Sufi Abdul Hamid did not need Japanese money. He had something better. For all his theatrics, Hamid had been a community organizer and under the slick mustache, the gold lined cape and his gleaming dagger—beat the heart of a union organizer.

What Hamid came up with was a combination labor union, employment agency, protection racket, Islamic cult and protest movement. With black unemployment in Harlem running as high as 50 percent, he offered to find jobs for black men who paid him a dollar. And to make sure they got hired, his men picketed businesses demanding that they get put on the payroll. Businesses which didn’t have a proper proportion of black employees were accused of racism and exploitation. Businesses which did were harassed anyway until they fired their black employees and hired Hamid’s men instead.

Hamid’s 125th street stepladder harangues intimidated Jewish store owners and customers, and many black customers as well. Whenever he succeeded, he picked up more recruits who might not have believed in his religious message, but liked the idea of getting a job. Businesses that paid up didn’t have to worry that the cape wearing hatemonger would show up in front of their store screaming violent threats. And so Hamid’s following grew. As did his bank account.

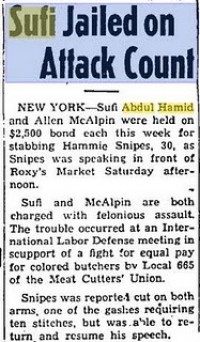

By 1938, Hamid had his own private plane and a white secretary. His union had gone through many names, from the Negro Industrial and Clerical Alliance to the Afro-American Federation of Labor. Adam Clayton Powell briefly joined forces with Sufi Abdul Hamid in labor protests and store boycotts, but Hamid was too power hungry to work with anyone for long. His rhetoric moved beyond anti-white and anti-Jewish racism to targeting light skinned blacks. Violent clashes with rival black unions led to Hamid’s arrest for stabbing Hammie Snipes, a former follower of Marcus Garvey turned Communist labor union organizer. And the courts barred Hamid from his picketing and forced him to focus his energies on his mosque. But in between, Hamid would play a role in Harlem’s first race riot.

By 1938, Hamid had his own private plane and a white secretary. His union had gone through many names, from the Negro Industrial and Clerical Alliance to the Afro-American Federation of Labor. Adam Clayton Powell briefly joined forces with Sufi Abdul Hamid in labor protests and store boycotts, but Hamid was too power hungry to work with anyone for long. His rhetoric moved beyond anti-white and anti-Jewish racism to targeting light skinned blacks. Violent clashes with rival black unions led to Hamid’s arrest for stabbing Hammie Snipes, a former follower of Marcus Garvey turned Communist labor union organizer. And the courts barred Hamid from his picketing and forced him to focus his energies on his mosque. But in between, Hamid would play a role in Harlem’s first race riot.

The Harlem riot of 1935

The Harlem riot of 1935 had many of the characteristics of the type. False information about police brutality circulated by radicals looking to stir up a mob. Looting misrepresented as a civil rights protest. And a swelling undercurrent of bigotry portrayed as outrage. As Congresswoman Maxine Waters would call the LA riots, “a revolution” and a “a spontaneous reaction to a lot of injustice”—Nannie H. Burroughs compared the Harlem riot to the Boston Tea Party and claimed that it was the duty of the oppressed to revolt.

The tactic was an old one, to unleash violence and then claim to be the only ones who could bottle it up again. Hamid had begun by intimidating storeowners with the threat of racial violence, but the race riot of 1935 would begin the intimidation of the entire neighborhood and eventually the entire city. Once unleashed and legitimized, the violence could no longer be bottled up again. A race riot before 1935 was an unusual phenomenon in Harlem. After 1935, it became far less commonplace. Next year when Joe Louis lost his first fight against Max Schmeling, Harlem rioters attacked white men in the street and dropped bricks from buildings on passing cars.

The 1935 riot would destroy as many black businesses as white ones. But that was the goal of the Communists who had played a major role in organizing the riot, who did not want to see black men reach the middle class, and of Sufi Abdul Hamid, who wanted to increase the scope of his protection racket. The courts had taken a dim view of his labor organizing tactics, but a race riot meant that stores could be hit up in a whole new way.

The riots and arsons went on for three days. Two hundred stores were destroyed and many more were looted, fires were set to cries of “Let it burn”. Entire businesses were wiped out. Some never recovered. The damage to Harlem’s business district was estimated at one million dollars. Bodies went to hospitals and morgues.

After the riot, Hamid began transitioning to a more moderate image. In an interview with the liberal Nation magazine, he disavowed bigotry and claimed to be a champion of the underprivileged. Liberal newspapers were all too eager to accept the nation that the riot was caused by oppression and economic conditions. The New York Times championed an aid package for Harlem. While some Jewish newspapers called the attacks a ‘Pogrom’, the socialist left wing Forward insisted on whitewashing the attacks as a protest against the authorities.

The judicial crackdown on Hamid’s labor extortion project refocused his attention on his mosque, the Universal Holy Temple of Tranquility

The judicial crackdown on Hamid’s labor extortion project refocused his attention on his mosque, the Universal Holy Temple of Tranquility, where he dubbed himself a Bishop. His nickname migrated from the Black Hitler to the Black Mufti. He married Queenie St. Clair, who ran Harlem’s numbers racket. Their marriage however ended badly when Queenie shot him, but failed to kill him. Hamid married again and bought a private plane, an obscene luxury at a time when many of those he claimed to help didn’t have enough to eat. But Hamid frugally kept it low on gas. The plane ran out of fuel over Long Island and crashed. Hamid died, survived by his white secretary who suffered only a broken elbow.

His new wife, a candle shop owner and fortune teller named Dorothy Hamid, who styled herself Madame Fu Futtam, and improbably claimed to be Asian, attempted to keep Hamid’s mosque going with visits that he reportedly made to her nightly from beyond the grave. Her prediction that Hamid would return from the grave in sixty days did not come true. Not long after the mosque had become a dance hall featuring a one legged dancer. Today the site at 103 Morningside Avenue is the home of St. Luke’s Baptist Church.

But though Sufi Abdul Hamid is mostly forgotten today, his legacy lives on

60 years later back on 125th street where the Black Hitler had delivered his stepladder harangues, the smashed windows and burning stores would find another ominous echo. In the winter of 1995—Al Sharpton and his National Action Network went to Harlem to lead a protest against another Jewish store, Freddie’s Fashion Mart. Sharpton denounced Freddie’s owner as a “White Interloper” in Harlem, protesters mimed tossing matches into the store, and one of them threatened to “Burn the Jew Store Down”. Finally one of the protesters pulled out a gun, ordered the black customers to leave and set the store on fire. Seven of the store’s mostly Hispanic employees died in the blaze.

Sharpton’s prominence was a testament to how mainstream Sufi Abdul Hamid’s tactics had become. When Obama visited Sharpton last week to celebrate the 20th anniversary of his National Action Network, he was commemorating not just the 20th anniversary of the Crown Heights Pogrom, but an organization which had ominous similarities to Hamid’s own.

The Freddie’s protests had been led by Morris Powell, who had been accused of Nazi type tactics. Powell ran the National Action Network’s Buy Black Committee, which echoed Hamid’s Don’t Buy campaign. Powell’s tactic of standing outside and screaming hatefilled slurs at passerby would have been entirely familiar to Hamid. “Keep going right on past Freddy’s, he’s one of the greedy Jew bastards killing our people. Don’t give the Jew a dime.”

Powell’s record goes back to 1984 when he broke the head of a Korean woman during one of his pickets. There is no doubt that Sharpton knew exactly whom he was bringing on board.

Sharpton too has more than a little in common with the Black Hitler. Like Hamid, Sharpton started out with a flamboyant personality, playing on bigotry while terrorizing storeowners and entire communities, building the perception of being the man who could unleash or tamp down racial violence, and then toned down the tactics which had power in exchange for political influence. Hamid never lived long enough to gain that kind of influence.. but Sharpton has become a major power broker in the city, the state and even nationwide, with Bloomberg funneling money to his National Action Network and Obama using him as his messenger to the black community.

The lesson of the Black Hitler is that such tactics pay off. Today Hamid is remembered as a pioneering union organizer. And Sharpton has been to the White House more often than any black leader. Sharpton’s gold medallion and Hamid’s turban and cape were showpieces. Their bigoted rhetoric and mob pickets a way of playing on violent populism. Self-interested protests whose goal is to boost the profile of a leader and the bank accounts of his organization have become the bread and butter of more mainstream leaders like Jesse Jackson. Their occasional outbursts of bigotry are forgiven for the power, protection and influence that they can bring to the table.

Even after the fire, Powell returned to Freddie’s screaming, “Freddie Ain’t Dead Yet”. The Black Hitler ain’t dead yet either. Not until his tactics are disavowed for good.

Daniel Greenfield -- Bio and Archives

Daniel Greenfield is a New York City writer and columnist. He is a Shillman Journalism Fellow at the David Horowitz Freedom Center and his articles appears at its Front Page Magazine site.

No comments:

Post a Comment